Barking Riverside development landscape

Contents |

[edit] Introduction

Designing urban landscapes to be resilient to climate change is an ever-increasing challenge in our crowded cities.

In the UK in particular, 19th century industrialisation along waterfronts created clear, defined borders between water and land, draining marshes and removing space for watercourses to expand. The majority of riverside developments have continued this approach; channelling water into tighter spaces to allow more plots for building.

However, the pressure for change is growing. An report by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) suggested that in the future London will experience hotter, drier summers and warmer, wetter winters leading to a significant increase in extreme storm events. The Mayor of London responded, publishing The Climate Change Adaptation Strategy for London outlining a requirement for more green spaces to reduce flooding, mitigate air pollution and urban heat island effects, and to connect ecological networks across the city.

Climate change and its potential consequences for our built environments means that the incorporation of flood mitigation measures into developments will be crucial; governments and developers will need to deliver more green spaces and water spaces. Waterside sites will need to balance sometimes divergent human, biodiversity, ecology and engineering needs. This balancing act between development and engineering requirements, people and ecology will set the landscape design agenda for the future.

[edit] Barking Riverside development

Part of Thames Gateway development project in east London, Barking Riverside, is a new development for more than 10,000 new homes, office spaces, schools and other public services for both existing and new residents. It is located on a brownfield site of 185 hectares that, prior to its industrial function, used to be part of the estuary and floodplains of the river Thames. Its location at the downstream end of existing creeks creates particular sensitivity to future flooding events.

The design team at Barking Riverside (see below) acknowledged the fact that for a sustainable design concept, a sizeable amount of land needs to be given back to water.

[edit] Building on a floodplain

The comprehensive landscape proposal for this site transforms the risk of flooding into a design feature of the development and park landscape. A solution has been developed with landscape in mind to link this partially-dismantled industrial site back to its former function as a floodplain connecting into the existing ecological network.

Together with the green corridors through the development and the incorporation of large street trees, the park area surrounding the development helps to establish sheltered local micro-climates and contributes to the reduction of the urban heat island effect. Additionally, the landscaped areas provide space for recreational areas, picnic zones, community gardens, walking trails and opportunities for informal education.

[edit] Designing with fluvial and surface water

It is the innovative strategy for both the fluvial and surface water which is key to the landscape’s success; mitigating the impact of future predicted climate change and shaping the new landscape. The development areas have been raised to protect the residents from fluvial flooding from the Thames and the existing creeks. The parkland incorporates flood compensation areas for when a heavy storm event coincides with the high tide this could result in tide-locked creeks creating serious flooding risks to the existing, neighbouring low-lying residential areas.

In order to avoid further flooding from heavy rain events, all areas of the new development discharge their surface water run-off into the parkland (instead of directly into the Thames). This area can store 100% of the surface water before it is allowed to discharge into the creeks during low tide.

[edit] Brownfield development

Because of its industrial history, Barking Riverside’s large areas of contaminated ground left limited scope for infiltration. In response, we utilised the Sustainable Drainage Strategy (SuDS) of providing restricted rates of discharge, to mimic more natural run-off patterns whilst improving water quality. The solution is a chained SuDS system consisting of living roofs, permeable paving, rain gardens, storm water planters and swales on the development platforms leading to attenuation ponds located within the lowered landscape. Open-water systems are given preference over permeable paving and underground storage, in order to contribute to human well-being and a rich bio-diverse habitat on site.

By employing water and storage capacities in diverse forms, from creeks to ponds, from basins to cascades, the risk of flooding is transformed into a design feature and one of the key characteristics within the landscape. These waterscapes create a contemporary interpretation in a form needed to establish sustainable water ecologies.

The solution incorporates two of these ‘water chains’, which gradually step down from the man-made platforms to the natural ecologically rich creeks: Buzzard Mouth Creek in the west and Goresbrook in the east. In form, function and habitat, this chained landscape works to highlight the natural evolution from the original low level estuary/marsh adjacent to the creeks towards the man-made landscape at the higher level, where hard water edges and straight lines prevail, reflecting the surrounding architecture. This evolution from creeks to floodplains, also informs the plant habitats, from native at the creeks to naturalized at the man-made levels and exotic planting at the highest part of the chain. The areas available for resident’s leisure activities are also graded, with people-oriented waterscapes, adjacent to sport areas and school buildings at the high level and limited access to the creeks at the lower levels.

[edit] Working holistically with water

When creating spaces for water the main tendency is to focus on the design of the water container; its engineered storage requirements and the visual quality and sounds it creates. However, working holistically with water involves designing for all its inherent qualities; creating opportunities for movement, incorporating the correct plants for cleansing, and allowing for deep water areas that will remain empty of plants in order to avoid algal bloom and high biological activity. But most importantly it must also create room for human activity.

[edit] Managing risk

There are inherent risks in creating areas of temporary, weather-responsive water storage in housing developments and parkland for both people and ecological habitats. So how can we design for accessibility without compromising human safety whilst avoiding exclusion barriers, or intrusive safety signage?

Gustafson Porter decided to incorporate deep ponds with permanent water at a high level for the benefit of residents, along with additional storage capacity. At the lower level the storage capacity is included in shallow pools and moist areas. We particularly wanted to avoid the proliferation of barriers, life-buoys and safety signs restricting human access to the water’s edge. Working closely with the Royal Society for Prevention of Accidents (RoSPA), we have designed a variety of water edges, ranging from boardwalks and stone quays next to areas of activity, to areas of soft edging, gradual slopes and aquatic planting in the parkland.

Within the development, the maximum water depth along the accessible edges never exceeds 600mm, whilst an additional flood warning system is provided within the natural parkland. Here, due to storage requirements, it was impossible to restrict the temporary water levels to only 600mm depth. A balance has been sought between access, safety and ecology. In order to avoid evaporation of the shallow ponds in the water-chain during warm summers, additional water will be pumped in, maintaining a continuous ecological habitat for wildlife.

[edit] Project progress

In 2009, Barking Riverside’s sub-framework plan for Stage 1, Stage 2 and the park landscape received planning permission from the Borough of Barking and Dagenham. Gustafson Porter trusts that the framework is strong enough to be maintained throughout all the issues which will arise during implementation. It must now prove robust enough to maintain focus on both the human needs and ecological requirements of this important site.

[edit] Lessons learned

Looking back on the master planning of Barking Riverside, the lessons learnt are an appreciation of the sheer quantity of space required and the necessity to provide an in-built flexibility within the design. Firstly, a solution which balances a lot of requirements for rain water and flood water storage, for human well being and safety, and for a rich biodiversity and undisturbed ecology needs a substantial amount of land commitment. Secondly, to meet goals set by Barking Riverside Ltd, the design team needed to achieve 50% of storage capacity upstream and 50% within the ponds. The fulfilment of this requirement became a balancing act with other requirements such as housing density. Due to space pressure the upstream ponds needed to change in some areas. However, our solution still ensures all levels and water volumes take future climate change predictions into account.

Reclaiming the waterfronts of the UK with sensitivity to people, wildlife and ecology will require commitment. The cost of developments is being weighed against that of holistic design. In the instance of Barking Riverside the existence of high-voltage cables slung over large pylons dotted across the landscape safeguarded the space required for a truly comprehensive solution. For London and other cities to adapt to an uncertain climatic future, space should be safeguarded – pylons or not.

[edit] Project team

Barking Riverside Ltd is a joint venture company between The Homes and Community Agency and Bellway Homes. With design and building contractors, they are currently developing the strategic master plan from Maxwan and the concept designs for stage 1 and 2 sub-framework plans by architects Sheppard Robson and Maccreanor Lavington, engineers Hyder and JMP and landscape architects Gustafson Porter.

[edit] Related articles on Designing Buildings Wiki

Featured articles and news

Retrofit 25 – What's Stopping Us?

Exhibition Opens at The Building Centre.

Types of work to existing buildings

A simple circular economy wiki breakdown with further links.

A threat to the creativity that makes London special.

How can digital twins boost profitability within construction?

The smart construction dashboard, as-built data and site changes forming an accurate digital twin.

Unlocking surplus public defence land and more to speed up the delivery of housing.

The Planning and Infrastructure bill oulined

With reactions from IHBC and others on its potential impacts.

Farnborough College Unveils its Half-house for Sustainable Construction Training.

Spring Statement 2025 with reactions from industry

Confirming previously announced funding, and welfare changes amid adjusted growth forecast.

Scottish Government responds to Grenfell report

As fund for unsafe cladding assessments is launched.

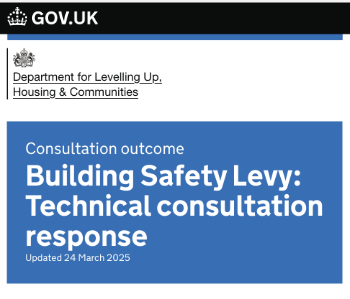

CLC and BSR process map for HRB approvals

One of the initial outputs of their weekly BSR meetings.

Architects Academy at an insulation manufacturing facility

Programme of technical engagement for aspiring designers.

Building Safety Levy technical consultation response

Details of the planned levy now due in 2026.

Great British Energy install solar on school and NHS sites

200 schools and 200 NHS sites to get solar systems, as first project of the newly formed government initiative.

600 million for 60,000 more skilled construction workers

Announced by Treasury ahead of the Spring Statement.

The restoration of the novelist’s birthplace in Eastwood.

Life Critical Fire Safety External Wall System LCFS EWS

Breaking down what is meant by this now often used term.

PAC report on the Remediation of Dangerous Cladding

Recommendations on workforce, transparency, support, insurance, funding, fraud and mismanagement.

New towns, expanded settlements and housing delivery

Modular inquiry asks if new towns and expanded settlements are an effective means of delivering housing.

Comments

To start a discussion about this article, click 'Add a comment' above and add your thoughts to this discussion page.